ETOOBUSY 🚀 minimal blogging for the impatient

Passphrases

TL;DR

Let’s talk about passphrases.

In security, a password is normally regarded as something that you know (and that others are supposed not to know). If anybody can prove to know the password, then it must be you.

Now, a single simple word as a password is a bit too trivial to attack. Even considering those large haystacks of words that can be found online, we’re still below one million words. At 1000 guesses/sec, this would mean 1000 seconds, that is less than 20 minutes to scan them all and less than 10 minutes to crack on average.

Why 1000 guesses/sec? It’s just a number of something that might reasonably be attempted on a weak web service exposed in the wild. But it might be a lot less if the service is not really prepared to serve that much traffic, and might be a lot more if we had our password leaked as a SHA-1 hash and our adversary had a lot of computer power. Let’s just take it as a reference for comparing stuff and scale things afterwards.

Now, there’s nothing stating that a password should be a real word. Here is where things get complicated and interesting.

On the one hand, we can tackle the problem by assuming that we generate

a sequence of N characters, e.g. 8 characters, each of which can be a

letter (either lowercase or uppercase), a digit, or a special

character like : or @. Sorry for my bias on the western world

folks, you can easily adapt it to your alphabeth or collection of

characters.

According to wikipedia, there are 95 printable characters in the basic

ASCII table (character from 0x20 up to 0x7E), so with 8 slots we end

up with:

distinct passwords. With the same calculation as before (1000 guesses/sec), on average it would take more than 100 thousands years to crack. Much better.

There’s just a little problem with this approach, though. Remembering

a password like 01234567 is admittedly very easy. Remembering

p;/7EdR& is definitely beyond the reach of most people. When we then

start also increasing the number of slots… it’s basically impossible.

Here there are several approaches that have emerged:

- generate something that seems like that. Like starting from a word

(

password) and making some changes here and there (P@s5w0:d). - use a password manager. It will remember the long, total gibberish password for us.

The first approach, which is widely adopted, is also definitely weak. Generating variations can be easy, so even trying out 1000 variations (which is generous) to a basic 8-letter word would mean, on average, below 12 days. Still quite far from that average 100 thousands years.

The second approach is sound, but still leaves us with the need to protect the password manager. Which can be tricky if we’re using an online password manager (but not only) and brings us to square one.

So, the real issue here is making passwords easier to remember. At least some of them. One approach might be to use a passphrase, which is still a sequence of characters (much like a password), but longer and formed by easily remembered words. According to the Wikipedia page for passphrase:

he modern concept of passphrases is believed to have been invented by Sigmund N. Porter in 1982.

There’s still passphrase and passphrase. Wish you were here and Mary

loves John make for some terrible choices, especially if an

attacker knows that we like Pink Floyd or that we’re Mary and we love

John.

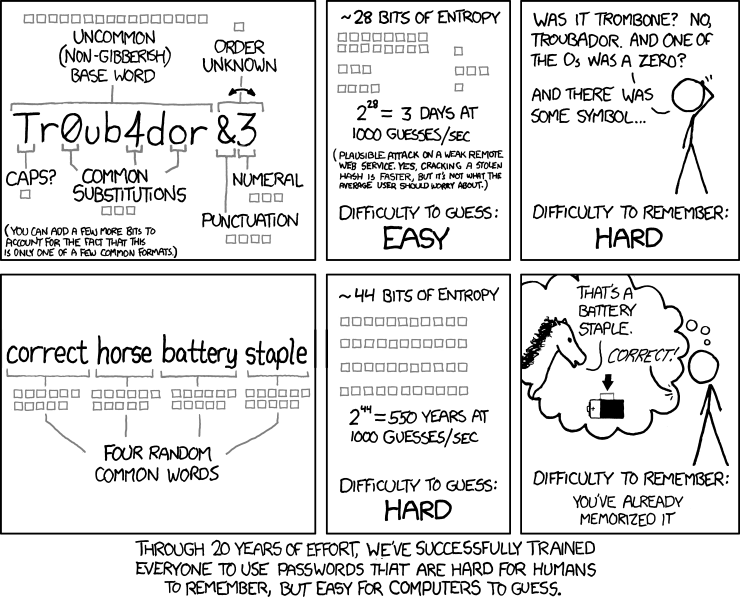

The best thing, to this regard, would be to come up with random words and form a passphrase with them. This is the gist of xkcd 936:

There’s been a whole lot of criticism about this approach, so here’s my humble take on it:

- it adheres to the Kerckhoffs’s principle so the evaluation of its strength does not depend on our attacker knowing that we’re using it

- the best way to attack it is through a dictionary attack, and actually this is exactly what it’s evaluated against.

Yet, some passwords that can be generated through that method might be

way weaker than others. Most notably, the very example correct horse

battery staple is now by itself an entry in any list of pre-computed

passphrases to try, so in the remote case in which it is generated

automatically (which, under the assumptions of the comic, should happen

once in about $1.76 \cdot 10^{10}$ cases, so we should be safe). This is

also the case for wish you were here, of course.

So, some combinations should be rejected, much like how we would reject real words when generating random 8 characters combinations. We will assume that they’re a small part though, so the approach proposed by XKCD gives us, on average, about 280 years to guess at 1000 guesses per second.

So well… yeah, passphrases are, in my opinion, a good way to come up with a password that can be both strong and easy to memorize.

Stay safe!